Here for you: a piece of writing about the process of writing… In the doing of it I’ll write about – and reflect upon – er, the writing of it. With examples of pieces by E. M. Forster and other Eng. Lit. heavies.

Post Modern maybe but I think all writing – good writing that is – starts from ideas. And those sparkles of inspiration don’t just call themselves into existence the moment you need them. At least not in my experience.

My ideas have to be worked at, wrangled, jostled into existence, thought carefully through, tenderly checked, and then written down. What follows is then a further round of brisk editing, correcting, and dithering. Someone once said, “The best copy-editing happens just after you’ve pressed ‘send'”.

But to start the process I either make a note somewhere on my laptop, send an e-mail to myself, scribble a line in my diary (paper & pen), or write on a scrap of paper I have handy and stuff it in my wallet.

If I don’t write something down the idea often gets lost, forgotten or confused. So, this piece is my thoughts about the process of creating ideas, keeping them, developing them, and nurturing them into a published form.

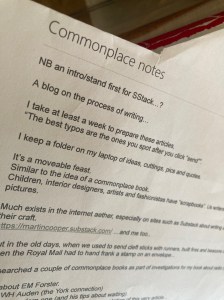

This essay started as a random scrawl across a computer file on the 22nd of last month. So on this occasion the birthing process has been around 23 days. Let me explain. Have a look:

I usually take at least a week – and often longer – to prepare these articles. So, you’ll see that the dateline on this piece is the 14th. Every month I publish a new essay on this date, close to the time of the month when the BBC pays its staff and freelancers.

That gestation period allows me to birth an idea, write notes, look at them, try writing something, adding photos and videos, and (a vital bit) checking – yet again – for mistakes.

So, on my laptop is a folder of ideas, cuttings, pics and quotes. Several folders in actual fact. They’re filed by date and by topic, sometimes both, and often neither. It’s an arbitrary system. For example there one MS-Word.doc that now runs to 14 pages with disparate paragraphs that I’ve either cut-n-pasted or typed frantically to capture an idea. At its side in that same folder sit various screen grabs, ‘phone pics, website links and audio clips.

It’s a big sloppy moveable feast. In some ways it’s similar to the idea of a commonplace book. I’m a bit late to the game on Commonplace Books, so forgive me if I over-explain.

Children, interior designers, artists and fashionistas have “scrapbooks”. Writers like us need words, although pictures are good as well. Sometimes. Those words form the basis of our ideas. And it’s the sparks of those very things that go to make radio programmes, news items, and exclusives.

They’re the ideas that end up in editorial meetings of programme planners, commissioners, and newsrooms. Each is a culture of its own.

I’ve previously written about the morning news meetings at the BBC. They can be frightening, intimidating, boring and an office-political-minefield for the uninitiated. Read this, about how one movie captures the era of 1980s BBC Radio News…

However, back to the art of writing and this literary thing called a Commonplace Book. I’ve capitalised it here because I want to highlight the concept.

I researched a couple of commonplace books as part of the investigations for my study of radio’s cultural influences over the past century.

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/radios-legacy-in-popular-culture-9781501388231/

I’ll do a proper “plug”, shill, and sales pitch for my book at the end of this piece.

But for now, this is my story about how research can end up being a captivating mystery. The rabbit hole of Commonplace Books, for me, began with the notion that a number of first-class writers have worked for the BBC – and they needed honouring.

George Orwell is well-known, of course, and indeed has a statue outside Broadcasting House in London. Others, too, have taken a Beeb paid contract including W. H. Auden, Virginia Wolf, Winifred Holtby, Louis MacNeice, and J. B. Priestley.

So, when – in particular – I was researching E. M. Forster I found useful comments he’d made in his Commonplace Book which he kept, on and off, from 1925 to 1968 (p. xiv). That was in addition to his diary (1909 – 1967). Here’s a few nuggets, some relating to radio broadcasting:

- Forster at times admitted to suffer from what today we’d call imposter syndrome. At one point in 1930 he thought that James Joyce had “something to say, but I am only paring away insincerities” (p. 87). Oh dear. I really wonder how the author of A Room with a View, Howards End and A Passage to India could worry so about the likes of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The latter, by the way gets a detailed mention in my book about Radio’s Legacy. See below.

- Throughout WW2 Forster wrote scripts for the BBC and broadcast regularly to India. He dismisses such work as “unimportancies”. He felt by 1943 that they were distracting him from writing another novel (p. 150).

- And like any avid listener he picked up on bad broadcasting, offering two examples of mangled English at the hands of the Beeb’s journos and contributors (pp. 123-4). Firstly, “A Naval Spokesman has looked forward to fewer Atlantic sinkings.” (9.00 PM news, 6-10-41) and then: “The defences of the Dutch East Indies are very far from being able to be ignored.” (Postscript 21-11-41).

And I’m certain that in keeping snippets like these a Commonplace Book can become both a second archive resource and a treasure of ideas for future inspiration.

In the next part of this series of articles I’ll mention W. H. Auden, with Robert Fripp (King Crimson) and David Byrne (Talking Heads) to come later. It’s not often you get to see those three in the same sentence. One way or another, each has collected and published thoughts, sometimes unconnected and a bit random, so that we can ponder how their brains work.

In the meantime, what we say on-air – and what others say about us as we speak through the microphone into the aether – is a recurring theme of my current book: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/radios-legacy-in-popular-culture-9781501388231/ .

Radio’s Legacy is the story of radio’s first 100 years as told through literature, movies, pop songs and art. You can get a preview – before you buy – about my methods. This link takes you to Chapter One – which is available to look at for free online: https://bloomsburycp3.codemantra.com/viewer/61c091c7

Thank you for reading. Do sign up to receive a new piece every month, like I say, around payday. And if you can spot a typo you can win a pen.

2 thoughts on “Radio & ideas – all our scrapbooks (Part 1)”