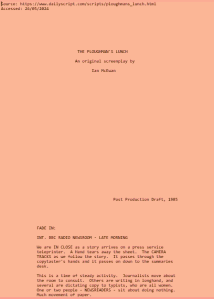

This is the last in a series of pieces about four decades of metro-media life in Britain: in which I come to some conclusions about Ian McEwan and Richard Eyre’s film The Ploughman’s Lunch – set in 1982 but cringingly relevant to the 2020s.

Do take a look at pages around this site, and consider subscribing to receive monthly articles about radio, culture, society and faith.

This piece asks a simple couple of questions. Have journalists always behaved so badly? Is this really what the public think of us?

The story in The Ploughman’s Lunch includes scenes filmed at that year’s Conservative Party conference in the aftermath of the Falklands/Malvinas War.

A rogue camera crew with Richard Eyre managed to get media passes to the Brighton conference. In the background the speeches play out, whilst in front of the camera we see Jonathan Pryce, Tim Curry, and Charlie Gore acting semi-improvised scenes in and around the conference hall.

I’ve already established that these media types: from BBC Radio News, London Weekend Television, and a Fleet Street tabloid not dissimilar to the Daily Mail, are thoroughly untrustworthy. You’d not want to lend their characters money or recommend them to your bank manager. Your mum and dad would draw a sharp breath if you tried to sing their praises over Sunday dinner.

So, what we have here is a film shot in 1982 and released in 1983 that highlights journalists who lie – both to their friends and to their work colleagues, who show disdain for provincial types, and who use mendacity as a means for personal advancement.

It is a direct and explicit critique of media practices.

Let me make three points to demonstrate that these “state-of-the nation” observations by McEwan and Eyre still have a critical relevance in the 2020s.

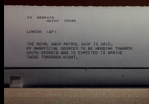

Firstly, the editorial standards and the perceived metro-centricity of the British Broadcasting Corporation. The film shows the morning editorial planning meeting in London as a type of university seminar with the professor/radio news editor surrounded by acquiescent acolytes – out of touch with the lived reality that much of the nation has to deal with every day. Let me quote McEwan’s stage directions from the post-production script:

Moulded plastic chairs are ranged along the walls of the room. Some journalists stand, some are half asleep. The feel of a morning assembly.

Seated at the only desk, by the door, sits the EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, while waiting he pretends to look at papers.

The tone of these meetings is restrained, weary. The Editor speaks with short pauses between each point. Quietly, as though talking to himself.

The cinema audience is presented with an image of a dull, male-dominated, inward-looking organisation.

That the BBC has been a London-based media organisation which doesn’t trouble itself much with events that happen north of Watford has long been a complaint. From my own experience it’s one that’s been voiced by listeners, viewers, and indeed by staff as well.

This has been a persistent criticism of the BBC from its inception and has in recent years – in part – prompted the Corporation to move programme departments to other centres away from London (BBC, 2021).

For example, at Salford the BBC now has CBBC/CBeebies, BBC Learning, BBC Radio 5 Live, BBC Sport, BBC Breakfast, and Religion & Ethics.

Radio 3 and the World Service Business Team also are based there.

In Cardiff, BBC Radio 4’s Saturday Live is now broadcast from there https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturday_Live_(radio_series), and Dr Who has long been filmed in the area.

Secondly, the personal integrity of journalists and their craft. Penfield is depicted as a BBC employee who is willing to lie, deceive, and cheat in order to advance his own career – and secure an exclusive for his book.

Forty years on, this resonates with allegations surrounding the manner in which former BBC journalist Martin Bashir secured an interview with Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1995.

The public repercussions have continued until the present day. It has in itself passed into popular culture: aspects have been fictionalised in episodes of The Crown, a Netflix series (Series 5, 2022), and Jonathan Maitland has written a play, The Interview, which was performed in 2023.

For me, journalistic integrity links to professional competence and to the broad and continuing discussions surrounding balance, fairness and independence. Indeed, these have been going on almost from the start of the BBC.

They surfaced during the 1926 General Strike, during World War Two, and again – and significantly for us here – during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

More recently there was the 2003 Iraq War dodgy dossier, the ensuing Butler Review, the Hutton Inquiry – and the eventual resignation of the then Director General, Greg Dyke.

I could also mention the 2014 Cliff Richard investigation and the Jimmy Saville controversy as well. There are other recent examples too, which at the time of writing are being investigated.

And thirdly, the perceived disdain by BBC network producers (and senior managers) of the journalism created at the Corporation’s forty local radio stations in England.

Penfield is shown in one scene interacting with women peace campaigners outside the RAF Greenham Common airbase in Berkshire. His car had a puncture and all he wanted from them was a jack to be able to change the wheel.

Later, back at BH, speaking to colleagues, he dismisses the protesters as being “cranks”, and the story “only fit for local radio, if that.”

It is this note of utter disdain which strikes a chord – even today.

From within the BBC an accepted career path is from the provinces to the centre: from local radio to network radio, Broadcasting House, and then to television. This hierarchy has existed – in my experience – for decades.

More recently however, media critics in in the past two years have accused the Corporation of effectively abandoning its English Local Radio network as it sought programme and job cuts through what it called its “Digital First” policy.

I’ve written about this at length in previous articles. New readers start here: https://prefadelisten.com/2023/08/14/bbc-local-radio-is-digital-first-the-end/

The idea was to reduce local programming by 50% to six hours per day and to reinvest the savings in expanding online journalism.

Some observers argued that the over-50s were adversely affected as they were the core local radio audience – who from habit preferred live radio to online digital platforms.

So, my conclusion runs something like this. The BBC itself has – throughout its history – been aware of the critiques of its journalism. These issues raised by McEwan and Eyre in 1983, as I’ve demonstrated, are not new by any means.

Indeed, they are enduring. Perhaps unwittingly the writer and director identified continuities in the ethics and morals of British journalism and media practice that in a number of instances have carried on for decades.

As an academic, journalist and broadcaster I applaud the vision of McEwan and Eyre, even as I cringe at the accuracy of their critiques.

Still, the Corporation continues to mount a robust defence of its newsgathering practices and its editorial policies. In my references (see below), I’ve linked to its page “Learn how the BBC is working to strengthen trust and transparency in online news”, which was last updated in 2017 and provides an explanation of its approach to trust, accuracy and best practice.

For more analysis of film and TV shows that feature radio – like The Ploughman’s Lunch – read my book:

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/radios-legacy-in-popular-culture-9781501388231/

You can also get a preview – before you buy – about my methods. This link takes you to Chapter One – which is available to look at for free online: https://bloomsburycp3.codemantra.com/viewer/61c091c75f150300016f10af

References

- Ian McEwan, “Screenplays, The Ploughman’s Lunch”, https://www.ianmcewan.com/books/screenplays.html

- Ian McEwan (1985), “The Ploughman’s Lunch, Post-Production Draft”, https://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/ploughmans_lunch.html

- BBC (2017), “Learn how the BBC is working to strengthen trust and transparency in online news”, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/help-41670342

- BBC (2021), “BBC to move key jobs and programmes out of London”, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-56433109

One thought on “Lies, radio news, and a pub lunch | part 5 of 5”