So far. We’re halfway through a series of pieces looking at the trade and craft of a radio journalist in the early 1980s. Life then is still relevant today.

That’s because I’m considering the rough terrain of morals, ethics, the BBC, Thatcher, and Yuppies – amongst other things.

You can read parts one and two of this series of essays by clicking here and here.

So, as far as our central “text” The Ploughman’s Lunch goes, I’ve identified three issues raised by this movie – each of which, I reckon, is still evident 40 years on (© A. Bennett).

In other words, and to digress, The Ploughman’s Lunch from back in 1983 is both prescient and enduring. Here’s a link to one version of the Bennett masterpiece I just mentioned as a digression: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yw5BVlOldLk. “Are you chewing, Charters?” Brilliant schoolmasterly disdain from Gielgud.

In this essay I’ll mention the team of actors, the writer, and the director of The Ploughman’s Lunch. I’ll also argue that the movie does three things:

- It raises questions about the editorial standards at the BBC, and particularly the metro-centricity of the national broadcaster.

- It allows us to watch the mendacity of individual journalists and to wallow in the perception of the lack of integrity in the trade.

- There’s also evidence of snobbery by some of the BBC network journalists in London towards the Corporation’s Local Radio operations.

Jonathan Pryce plays the central character James Penfield. It’s an early career piece – before roles such as the governor in Pirates of the Caribbean and his part in Game of Thrones.

In The Ploughman’s Lunch he plays an ambitious BBC Radio News producer responsible for the hourly summaries on Radio 4. Outside of work he’s writing a book with an alternative – improbably positive – narrative on the Suez Crisis. That works in The Ploughman’s Lunch to contrast the actual failure of Suez with the real British victory in the South Atlantic.

Tim Curry plays the debonair and slightly rakish journalist, Jeremy Hancock, who thwarts Penfield’s attempts to get the girl. Curry is well known for his appearances in the stage and film versions of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975). He also played a New York radio DJ in the 1980 film Times Square about two teenage runaways in the punk era.

Charlie Dore is known both as a musician and an actor. Her character here is Susan Barrington, a self-assured, somewhat snobbish researcher at London Weekend Television. As a singer/songwriter Charlie Dore’s 1979 single, “Pilot of the Airwaves” was long a turntable hit and a favourite of radio DJs.

The end of The Ploughman’s Lunch has Barrington and Hancock locked in a passionate embrace at the Brighton Conference Centre – to the disappointment of Penfield, the BBC journalist from a working-class family. The subtext: class and wealth always trump education.

Earlier Penfield had pleaded with her to spend the night with him. When she declines, he asks in a patronising manner:

“You don’t trust me?”

She replies, “I don’t trust anyone. That’s what comes from working in television.”

He’s crestfallen and says perhaps somewhat defensively in an attempt to win the verbal exchange, “On no, in radio we’re different.”

She ripostes with a cynically dismissive “Oh yeah?”

The undercurrent is actually that both are lying – about their own integrities and that of their media outlets.

The screenplay is written by Ian McEwan and marked a shift in career. From around this time his output broadened to tackle a number of what might be termed social commentaries: critiques of contemporary society and its values.

Sometimes courting controversy, he’s addressed issues ranging from the Middle East, religion, political Islam, atheism and the environment, as well as politics – both in Britain and abroad.

The Ploughman’s Lunch sits alongside a number of his other possible “state of the nation” pieces. These include Saturday (2005 – set amidst demonstrations in London against the Iraq War), and – according to some, The Child in Time (1987 – about pressures on relationships in mid-1980s Britain).

In this respect, critic Michael Ross (2008) has drawn a link between these works by McEwan, and both Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1855) and Charles Dickens’ Hard Times (1854). The narrative style here is to present a story that involves a relatively tight-knit circle of friends and/or family and their interactions with real contemporary events (Ross, p. 75).

By the way, McEwan is a writer who is self-aware of his cultural standing. So much so that he maintains a website which has links to academic and scholarly studies of his work. There is even a link on there to the York Notes A-level study guide to his own novel Atonement. Follow this link in blue and it’s down at the bottom: http://www.ianmcewan.com/resources/booksabout.html

And read about his screenplays here: http://www.ianmcewan.com/books/screenplays.html

The director of The Ploughman’s Lunch is Richard Eyre.

He has a long track record as a theatre director at Edinburgh, in the West End, and at the Nottingham Playhouse (where Jonathan Pryce worked for a time early in his career, and my parents took me as a kid in the early 70s to see some classic performances). He’s also been the artistic director at the National Theatre on London’s South Bank. Sir Richard was on the BBC Board of Governors from 1995 to 2003.

The Ploughman’s Lunch was his film debut, and he has since worked on a number of other film and TV projects – including Shakespeare plays and adaptations of contemporary British novels.

Eyre’s directorial style in The Ploughman’s Lunch has provoked one critic – Stephen Shafer (2001) – to see similarities with Room at the Top (1959). Both movies do indeed present the struggle of the working classes.

However, whilst the adaptation of John Braine’s novel showed the upward struggle of an embittered social climber, McEwan and Eyre’s The Ploughman’s Lunch shows the decline of the working class amidst the rise of what became known as the Yuppies of the Thatcherite era (Shafer, p. 11).

At the Tory party conference in Brighton, it is the privileged and rich who succeed. Working-class Penfield, however, achieves no redemption: he has lost those friends and family close to him, and has learned no moral lesson.

Next time: I’ll discuss other academic viewpoints and approaches to this film. We’ll be talking about “lacking moral perspective”, “the anxiety of the present day”, “the falsification of the past”, “a bankrupt consensus”, and “a film without any character who is in the least possible way likeable”. Nice.

So, this has been a quick summary and example of how – in this case – university academics spend their time and the nation’s money by watching old movies. (That last sentence was a joke based on irony and sarcasm. Just to be clear.)

For more analysis of film and TV shows that feature radio – like The Ploughman’s Lunch – read my book: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/radios-legacy-in-popular-culture-9781501388231/

You can also get a preview – before you buy – about my methods. This link takes you to Chapter One – which is available to look at for free online: https://bloomsburycp3.codemantra.com/viewer/61c091c75f150300016f10af

By the way, whilst we’re on the subject of the trade and the craft of journalism, I was struck by a new book by Yuval Noah Harari that considers the links between truth, disinformation and lies. This book is published in 2024, and links nicely with a few of the ethical issues raised by The Ploughman’s Lunch.

Let me be clear, in true hack-style I’ve not actually read the work I’m about to comment upon. That’s a trick perfected by the great Alan Partridge, when he said to one of his guests,

“I read a bit in your book that was highlighted in yellow by a researcher for me.”

And then wondered why the celebrity threw a huff. (Knowing Me, Knowing You (1992), BBC Radio 4, S1, Ep1, 1 December) Read more on p. 153 of my research as part of the chapter called “Hang the DJ”.

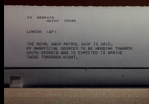

Instead, I’ve read a review in The Economist. The book in question is Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari, and the article was on p. 79 of the print edition of the newspaper dated Sept 14th, 2024. Here’s a photo to prove I looked at the newspaper.

Harari writes about information: about facts, and about disinformation. His viewpoint goes like this: information, in and of itself, isn’t truth – however you may care to present it. It may or may not be “facts” either.

So, “The moon is made of blue cheese” is information, but it’s neither truthful or factual. I either assume this to be so, or I know it because Elvis told me. See what I did?

The review makes clear that a central heuristic of Harari’s work is that information, of itself, doesn’t represent anything.

By thinking that way you can get away from asking “what is truthful?” and “what is a lie?”. Because that way you just overload yourself with even more information without trying to find out what’s really going on. Rabbit-hole syndrome.

Instead, the book argues that information is a way of linking, of connecting, and organising ideas. So, information technologies such as oral traditions, clay tablets, print, newspapers, and – yes – radio are ways to create some sort of social order.

Hence, the weather forecast on this morning’s breakfast show told me it would continue to rain for the rest of the day. Using the information presented I could bring comfort and dryness by taking an umbrella when I left home. Or I could just go back to bed. Either way there’s order in my life.

I’d also add the following observation: because The Ploughman’s Lunch deals with characters who spend their lives avoiding the truth there is very little social order in their existence.

Read more about journalism, radio, movies and pop songs in my book.

And don’t forget to sign up to receive these articles every month. Put your details in the “subscribe” box. Thank you for reading.

References

Ross, Michael L (2008), “On a Darkling Planet: Ian McEwan’s Saturday and the Condition of England”, Twentieth-Century Literature, 54:1, pp. 75-96.

Shafer, Stephen C. (2001), “An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960s to the 1980s: From Class Consciousness to Marginalization”, International Labor and Working-Class History, No. 59, pp. 3-14.