…bear with me this once. This article will appear to be joyously off-topic at the start because it won’t mention much about radio; just superheroes. The reason is I want to talk about finding reality in fiction. On the face of it that sounds like nonsense, but if I try to explain I hope you’ll see what I’m driving at.

As an example let’s take the 2017 movie Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 produced by Marvel Studios and distributed by Walt Disney. It’s a great movie by the way, and helped by a nostalgia-driven 1970s/80s soundtrack that get’s the ‘music of your life‘ emotions turning.

The question I’ll wrestle with here is what does this sci-fi film tell us about life today? About our own mortality and existence? In two hundred years time what would a sociologist make of the film? I’m interested in finding out what the ‘real’ in the fiction says. To be specific, I’m not asking whether the plot is realistic; it’s not. But rather how the story is built upon actual things that I can watch, identify with, and make meaning with.

I can accept that that the computer-generated images of a raccoon and a monosyllabic twig are comedy characters. And I agree that Drax the Destroyer is a big muscle-bound thug with a twinge of meloncholy about him. I’ve met people like that in real life. On the other hand I live in Yorkshire, England, and the name Drax makes me think of a huge electricity-generating power station. Weird. But that’s why reality and meaning are in many ways specific to the individual. Having said that, of course, there are a number of universal truths available to viewers of the film.

As to the story itself, I can interpolate the search for family, father-son relations, loss, grief and anger. And the universal reality that families-are-complicated-and-can-sometimes-break-your-heart-but-they’re-really-important-so-we-need-to-work-hard-at-sorting-it-out-one-last-time-for-the-sake-of-everyone. These meanings emerge from the fiction, and present themselves as real and truthful representations of our own human condition. The creation, or production, of a reading of this film emphasises the link between language, reality and meaning. The fictional characters talk in a way that I understand, the scenes show an emotional reality I can recognise, and the sum is – for me – a film I can relate to.

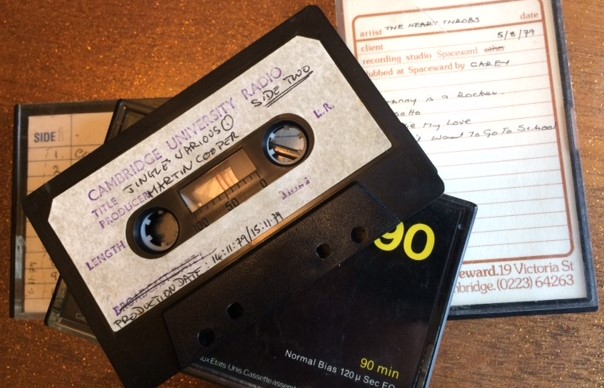

This is called critical realism and my thoughts here are driven by a chapter written by Garry Potter called “Truth in Fiction, Science and Criticism”, in José Lopez and Garry Potter (eds.), After Postmodernism: An Introduction to Critical Realism, The Athlone Press: London, 2001, pp. 183-195. So, to carry on this point, I can consider the opening scene of GoTG2 as an example. I’ve mentioned it in a previous article. It’s a flash-back to the 1980s and the rural mid-west of the USA (and this bit sticks fairly close to the comic book version of events). The girl Meredith is riding along in an open-top car with her boyfriend. He happens to be a good-looking long-haired space alien with sunglasses (but that’s not important right now; later he’s revealed as the ruggedly-handsome silver-haired evil father of Peter the hero of the film). For now the two young lovers with the wind in their hair are relaxed and care-free. They’re singing along to Brandy You’re a Fine Girl by Looking Glass, from 1972. It was a number one hit in the USA, but failed to even get in the top fifty in the UK. I know it in Britain from listening to RNI (Radio North Sea International), a pirate radio station broadcasting to the UK in the early 1970s. It was played to death as what the radio industry calls ‘a turntable hit‘. In the movie it’s on a ‘mix-tape‘ cassette (a redundant technology in the UK and USA by 2017, but ubiquitous in the 1970s and 80s) which adds detail to the period reality – although I don’t recall them being called mix-tapes in Britain until at least the late 1990s. It was Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity that talked of the aesthetics of making the perfect tape, and we used to call them ‘compilations’, if we called them anything at all, or ‘my tape that I’ve just made’. So this song by the band Looking Glass is presented here as being a ballad of happy romantic innocence, of times gone past – and that strikes a resonant chord with your correspondent. I recall those times myself, and how the song spoke to me in those years of teenage innocence. The short film sequence evokes a longing for things lost, and of memories themselves so strong you could almost – as it were – touch them. Those things are real to me, and they make me think of my own early twenties and how I’d be the same generation as Peter’s dad – which is either weird or daft because he’s an alien and I’m not.

So this song by the band Looking Glass is presented here as being a ballad of happy romantic innocence, of times gone past – and that strikes a resonant chord with your correspondent. I recall those times myself, and how the song spoke to me in those years of teenage innocence. The short film sequence evokes a longing for things lost, and of memories themselves so strong you could almost – as it were – touch them. Those things are real to me, and they make me think of my own early twenties and how I’d be the same generation as Peter’s dad – which is either weird or daft because he’s an alien and I’m not. The music also makes me think of listening in to pirate radio on my mum and dad’s HMV valve radio. This scene is therefore real for me because of the production I’ve made to create that personal meaning and mental imagery.

The music also makes me think of listening in to pirate radio on my mum and dad’s HMV valve radio. This scene is therefore real for me because of the production I’ve made to create that personal meaning and mental imagery.

So what film, movie, book or song has presented a reality to you? Let me know in the comments section below.

so many, I’ll need to think. Thanks Martin, thought-provoking… Nice piece!

LikeLike

Well spotted. Sorted. Thanks. M

LikeLiked by 1 person